New Drugs, New Devices

By Ted Rosen, MD

The year 2017 saw many new drugs and devices introduced that show considerable promise for dermatology patients. A fast round-up of what was approved in 2017 (including one December 2016 entry) appears in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Drug | Brand | Approval Date | Indication/Area | What’s New |

| Crisaborole | Eucrisa® | 12/14/16 | Atopic dermatitis | Good safety data, no limit on therapy duration, safe for use on face and eyelids, etc. |

| Dupilumab | Dupixent® | 3/28/17 | For moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, approved for adults only, minimal adverse events | |

| Guselkumab | Tremfya® | 7/13/17 | Psoriasis | Superior to adalimumab for achieving PASI75, PASI90, and PASI100 (44% achieved PASI100 at 24 weeks) |

| Brodalumab | Siliq® | 2/15/17 | Similar results as guselkumab | |

| Blue Control Device

|

7/13/17 | Wearable blue light for psoriasis | ||

| Delafoxaciin | Baxdela® | 6/19/17 | Antibiotic | Fluorinated quinolone, wide spectrum |

| Ozenoxacin | Xepi® | 12/14/17 | Non-fluorinated quinolone, cream for impetigo | |

| Oxymetazoline | Rhofade® | 1/19/17 | For persistent facial erythema of rosacea | |

| Benznidazole | Not branded | 8/29/17 | Chagas disease | Oral agent to treat tropical disease |

| Avelumab | Bavencio® | 3/23/17 | Merkel cell carcinoma | New treatment for aggressive neuroendocrine cancer |

| Pembrolizumab | Keytruda® | 3/14/17 | Hodgkin lymphoma | Expanded indication for adult and pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma |

| H202 40% | Eskata® | 12/17/17 | Seborrheic keratosis | Topical solution, 40% solution most effective, 41.3% of lesions clear or near-clear |

| HZ/su Vaccine | Shingrix® | 10/20/17 | Shingles vaccine | May be more effective than current vaccine |

| Dignicap Cooling Cap | 7/3/2017 | Chemotherapy-induced alopecia | 70% of chemotherapy patients expected to lose all of their hair retained at least 50% of scalp hair | |

| DermaPACE device | 12/28/17 | Diabetic ulcers | 48% of patients had >90% healing at 20 weeks | |

Note that trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

The “libraries” of therapeutic options for many conditions are being expanded, such as the treatments for atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and cutaneous cancers. With the wealth of new options comes the need to learn how to best deploy these new drugs and devices for use in our patients. A few highlights follow.

Crisaborole

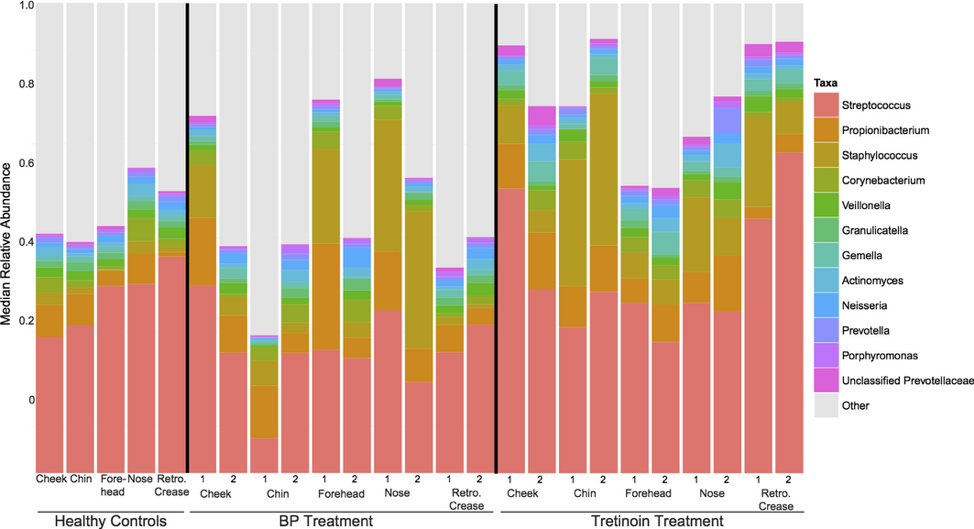

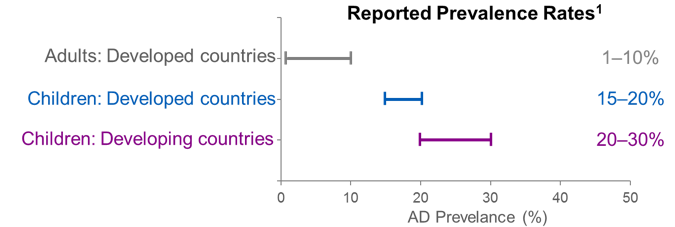

Atopic dermatitis can be a lifelong condition and one that distresses patients by its appearance as well as by itching. Crisaborole, a nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor, is indicated for patients with atopic dermatitis of at least two years duration. There is no skin atrophy, so it may be safely used on the face, eyelids, skin folds, and external genital areas. It is to be used twice a day and there is no limit on how long therapy may persist.1 See Figure 1 for atopic dermatitis patients treated with crisaborole by the author.

Dupilumab

Dupilumab is indicated for moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults; it is a monoclonal antibody that works against subunit 4Rα of the interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 receptors. It reduced pruritus markedly compared to placebo and the once-weekly and twice-weekly regimens provided about equal effectiveness.2

Avelumab

Avelumab is an anti-programmed cell death (PD)-ligand (L)1 immunotherapeutic agent that has been approved for use in pediatric (≥ 12 years) and adult patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma, an aggressive neuroendocrine cancer with high morbidity and mortality rates. Complete response occurred in 10/88 patients in a phase II trial and 19/88 had partial responses with median overall survival rates of 12.9 months.3

Cemiplimab

This anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody is used to treat unresectable locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. It is not yet approved but early results hold great promise as the objective response rate in phase I was 46.1%. A phase II pivotal study is currently enrolling. The most commonly reported side effects are fatigue, arthralgia, and nausea.4

Important Trends in 2017

- The armamentarium of agents is building up, giving us more choices and likely improving treatment for patients

- Many drugs are now being tested against active comparators—these head-to-head studies provide relevant and valuable clinical information (such as the study that showed guselkumab was superior to adalimumab in achieving PASI75, PASI90, and PASI100)

- Indications may expand, for example, guselkumab is being investigated now for its potential utility in treating psoriatic arthritis

References

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016;75(3):494-503.e494.

- Beck LA, Thaci D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371(2):130-139.

- Joseph J, Zobniw C, Davis J, Anderson J, Trinh VA. Avelumab: A Review of Its Application in Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 2018:1060028018768809.

- Kaplon H, Reichert JM. Antibodies to watch in 2018. mAbs. 2018;10(2):183-203.