Pediatric Acne: Putting Best Practices into Actual Practice

By Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD

Restaurants do it all of the time—something changes and the restaurant must understand the change, adapt to it, and make changes to its system. Changes may seem unimportant—a decrease in local foot traffic, changes in customer preferences for certain foods—but they can impact business. When the change is well managed, the restaurant recognizes it and responds accordingly. If it does this well, the consumer experience remains optimal, the restaurant retains or expands its business, costs are controlled, and outcomes remain favorable.

Why don’t we do this in healthcare? Specifically, why don’t we do this in the field of pediatric acne?

Here’s what has changed:

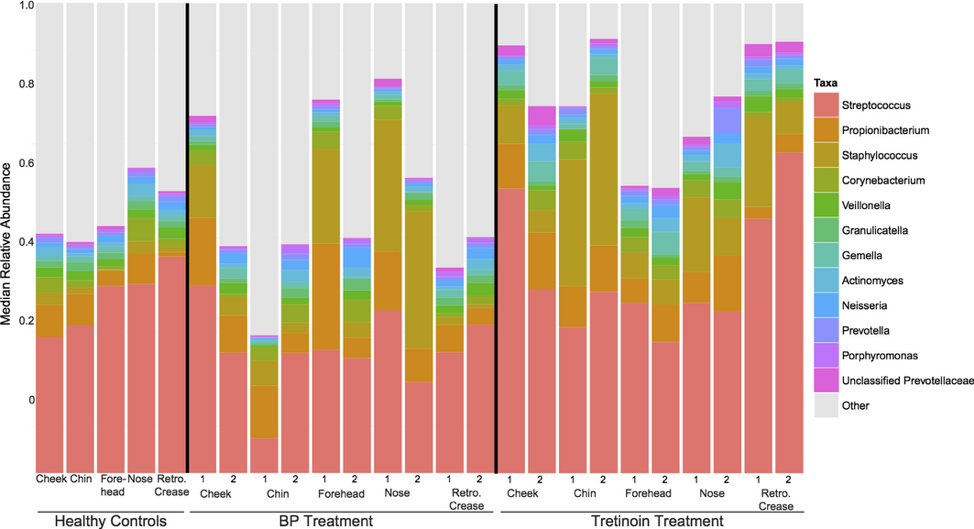

A great deal has been elucidated recently about the preadolescent acne microbiome. Preadolescents with acne tend to be colonized with a greater diversity of cutaneous bacteria than control patients; in particular, Streptococcus species are more prevalent. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Preadolescent microbiome for acne for healthy controls, acne patients treated with benzoyl peroxide (BP), and those treated with tretinoin. Note that 1 and 2 indicate first visit and pretreatment while 2 indicates the second visit.1

In a study of girls between the ages of 7 and 12 with at least six acneiform lesions performed by Ahluwalia et al, patients were treated with benzoyl peroxide (BP) 4% for six weeks (range four to 8 weeks). They were administered a swab to assess the microbiome at week 0 and then at the end of their treatment. This study found that patients with more acneiform lesions were significantly more likely to have more P. acnes bacteria and there were trends toward decreased S. mitis and increased S. epidermis. This has led to the intriguing observation that P. acnes seems to create a hostile environment for certain pathogens—but allows Staphylococcal strains like S. epidermis to flourish.1 This seems to suggest that early preadolescent acne may involve a shift from a dominant S. mitis in the microbiome to a dominant P. acnes, which is then accompanied by more acne lesions.

Another change has been the switch of BP from a prescription medication to an over-the-counter (OTC) product, as well as the introduction of OTC retinoids (adapalene). OTC products are a cornerstone of acne treatment, but patients seem somewhat less consistent at acquiring OTC products as compared to prescriptions.. In a cohort study of 84 patients (ages 12 to 45) seen in a dermatology clinic for acne, patients were contacted by phone two weeks after their appointment. All patients had been counseled by the dermatologist to purchase an OTC BP product as part of their treatment. Only 20% of the patients remembered what OTC product was recommended and about a third (36%) did not purchase any OTC products, although 93% picked up their prescriptions. Of the 64% of patients who reported that they did buy an OTC acne product as recommended, only 32% of these products contained BP.2

Here’s what we can do:

Knowing more about the microbiome, better and more targeted medications can be developed. The antimicrobial effects of BP have been shown to be equivocal.1 Nevertheless, BP is a key part of acne treatment. BP is now available OTC and patients must be educated that it is an important element in acne treatment and that they must read labels or follow instructions to be sure to get the right OTC product. Some ideas to improve this situation are samples for patients to take home and handouts or other printed materials with product images so the patient purchases the right OTC product.

Pediatric acne guidelines are in place.3 There is a large body of evidence in the medical literature about how to treat pediatric acne. However, in medicine, there is often a time lag between the validation of medical evidence (including published clinical trials and updated guidelines) and their implementation. For example, it took over 15 years for the use of beta-blockade following myocardial infarction to translate into practice as a standard of care for the average heart attack survivor.

Pediatricians are on the frontlines of caring for pediatric acne. While patients can be referred to a dermatologist, it may be more efficient and convenient for patients if the pediatrician could manage these cases efficiently. To that end, these pearls are offered.

- Pediatricians and the clinicians who work with them should be trained with respect to the guidelines on pediatric acne

- Training materials for patients should be developed—it would be ideal if these could be ordered via electronic medical records

- In particular, training materials should offer images of OTC products, if recommended, to assure patients select the right medications

References

- Coughlin CC, Swink SM, Horwinski J, et al. The preadolescent acne microbiome: A prospective, randomized, pilot study investigating characterization and effects of acne therapy. Pediatric dermatology. 2017;34(6):661-664.

- Huyler AH, Zaenglein AL. Adherence to over-the-counter benzoyl peroxide in patients with acne. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2017;77(4):763-764.

- Eichenfield LF, Krakowski AC, Piggott C, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric acne. Pediatrics. 2013;131 Suppl 3:S163-186.