Psoriasis Update: Current Therapies

Bruce Strober, MD, PhD

At Maui Derm 2015, Dr Strober led the psoriasis panel with a discussion on current therapies.

Apremilast

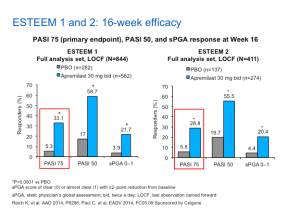

Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibitor, was approved for psoriatic arthritis in March, 2014 and subsequently approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis in September, 2014. The data for apremilast rests on two major Phase III studies, ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2. Patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (PASI = 12, BSA =10%, sPGA =3) were randomized 2 to 1 to apremilast 30 mg twice daily or placebo. At week 16, all placebo patients switched to apremilast 30 mg through week 32. At week 32, all patients who achieved PASI-75 were randomized (1:1, blinded) to continue apremilast or receive placebo. Upon PASI-75 loss, patients who were re-randomized to placebo resumed apremilast treatment.

The efficacy (PASI 75 achievement at 16 weeks) of apremilast in either study (ESTEEM 1/ESTEEM 2) is somewhere around 29% to 33% and placebo is around the 5% to 6% range. Apremilast demonstrated an acceptable safety profile and appeared to be well tolerated for up to 52 weeks.

Within these studies, subanalyses were performed looking at nail, scalp and palmoplantar psoriasis based on the NAPSI, ScPGA, and PPPGA. Apremilast demonstrated significantly greater response rates versus placebo for psoriasis affecting the nails, scalp, and palmoplantar areas among patients with NAPSI ≥1 (n=266), ScPGA ≥3 (n=269), or PPPGA ≥3 (n=42) at baseline, respectively. This data demonstrates reduced severity in nail, scalp, and palmoplantar psoriasis at week 16, and observed improvements up to week 32. Keep in mind that the patients in this study with palmoplantar psoriasis were seen in the context of also having moderate-to-severe psoriasis; these are not patients with bona fide, stand-alone palmoplantar psoriasis.

Overall, the drug appears to do well on various parts of the body, much like our other good psoriasis medications.

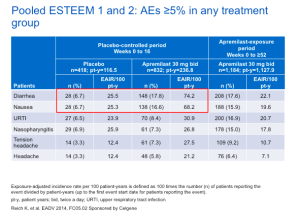

When you’re discussing apremilast with your patients, there are two side effects that seem to appear to be most troublesome—diarrhea and nausea. Over the course of the study, approximately one in six patients experienced diarrhea or nausea; however, probably fewer than five percent of patients found it intolerable and very few patients discontinued this drug due to either side effect.

Most commonly, these side effects occur during the first one to two months of therapy. There are no real “studied” approaches to minimizing these side effects; however, after the first of couple of months, the side effects did tend to wain.

Apremilast: Effects on Itch

Psoriasis patients have reported itching as the most bothersome symptom of psoriasis. (Lebwohl MG, JAAD. 2014) A pooled analysis of VAS of itch from ESTEEM 1 and 2 demonstrated improvements in pruritus with apremilast as early as week 2 and maintained through week 32. The reduction of itch in many patients precedes the clearing of their skin.

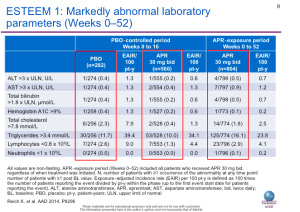

Additional Considerations with Apremilast

As previously noted, apremilast demonstrated an acceptable safety profile and was generally well tolerated for up to 52 weeks with no new or unexpected safety findings. In Dr Strober’s opinion, you should perform baseline labs prior to starting any medicine for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. This is, in part, due to the fact that you may have to switch drugs if they do not respond to the initial therapy. Current data show no indication for a need for laboratory monitoring with apremilast, as no organ- or system-specific toxicities have been detected.

One of the two warnings on the label for this drug is the risk for depression or thoughts of suicide. Another pooled analysis of the ESTEEM 1 and 2 trials studied psychiatric disorders and depression with the use of apremilast. There is a slight increase in frequency of depression with the patients on apremilast versus placebo (1.2 % to 0.5%). Based on an analysis of clinical trials of apremilast and the published literature on psoriasis, there is no evidence of an increased risk of psychiatric events, including suicide, with the use of apremilast. The rate of depression was comparable to the background rate in the psoriasis population. People often ask about this issue, but Dr Strober feels that depression and mood effects of apremilast are possible, but are relatively rare. This should be discussed with the patient at the baseline visit, and followed prospectively.

One important way of looking at the data is to consider how the drug affects the population overall with regards to symptoms of depression. The PHQ-9, a patient-reported questionnaire, has been very well accepted, according to the medical community, as a very reliable, subjective means to detect depression. Using the PHQ-8, a similar study lacking one question found in the PHQ-9, invesigators found that psoriasis patients receiving apremilast achieved significant improvements in the PHQ-8 total score compared to those receiving placebo—indicating that their depressive symptoms may improve over the course of therapy.

Weight loss is another warning in the apremilast label. While weight loss has been observed in the ESTEEM trial (approximately one in five to six patients), there were no significant clinical consequences observed from the weight loss. The average weight loss over one year of therapy across all study subjects receiving apremilast is about four pounds. When discussing this drug with your patients, this is an issue that should be mentioned. Weight loss did appear to level off over time and it was not correlated with diarrhea/nausea. One cannot predict who will experience weight loss, and this side effect affects patients of both high and low BMI. Of note, only two patients in the clinical studies discontinued apremilast because of weight loss.

Drug Survival

Dr Strober concluded his presentation by discussing a few posters that have been presented over the past year regarding drug survival. According to Dr Strober, “one of the biggest failings of the medicines that we use for psoriasis is that they don’t always keep working.”

Which drugs do the best when looking at analyses?

There are three different analyses out there and they’re all corroborating one another. The first study (van den Reek and colleagues) aimed to describe one-year drug survival for adalimumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab in a daily practice psoriasis cohort. The other objective was to introduce the concept of ‘happy’ drug survival defined as DLQI≤5 combined with being ‘on-drug’ at a specific time-point. 249 patients were included in the study. The patients were asked how ‘happy’ they were over a course of time, i.e., 1. remained on the drug and; 2. DLQI was reduced to less than or equal to five.

Of note, your average patient, when he/she enters a clinical study for moderate to severe psoriasis, has a DLQI in the 10 to 13 range. If you are able to bring those patients to less than or equal to five, then you are achieving a measurable and clinically significant improvement in quality of life.

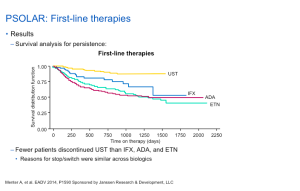

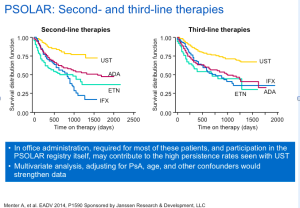

In this study, at baseline, the majority (n=115, 73%) was considered ‘unhappy’ and the minority ‘happy’ (n=42, 27%). The percentage of ‘happy’ on-drug patients increased to 79% after 1 year. In summary, ustekinumab showed better overall drug survival compared to etanercept and a trend towards better overall drug survival compared to adalimumab. Why do we suppose we may see these results? We must keep in mind that in these studies there is no randomization. Secondly, does the frequency, setting and method of administration make a difference? With ustekinumab, a subcutaneous medication commonly is administered in the office every 3 months. This set of features may allow patients to stay on drug longer. We should also consider whether or not the DLQI is a valid means to measure happiness and drug survival.

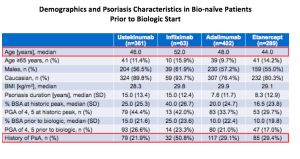

A multicenter, longitudinal, observational study, PSOLAR, evaluated persistency, i.e., treatment longevity, of biologics for psoriasis. While this study was funded by Janssen Biotech as part of the post-marketing surveillance for ustekinumab, it is important to note that over seven hundred patients were on drugs other than ustekinumab.

Again, this was not a randomized study, and patients were “channelled” to the various therapies based on “real world” clinical decision making. The results show that the persistence of ustekinumab therapy in PSOLAR was significantly better than anti-TNF therapies in biologic- naïve and experienced psoriasis patients, with lower rates of stopping/switching and higher median days on therapy.

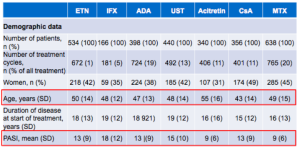

In a third study, the researchers aimed to describe and compare the drug survival of different biologic (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab,and ustekinumab) and systemic drugs (acitretin, cyclosporine, and methotrexate) in moderate-to-severe psoriasis by analysing data from the BIOBADADERM registry. 1956 patients were included in the analysis (1240 on biologics and 1076 on classic drugs) with a median follow-up time of 3.3 years. When looking at the demographic data, you can see age differences across the board as well as widely varying PASI scores. Patients with more severe disease appeared to be going on infliximab with other less severe patients going on other biologics or even acitretin.

Over half of these patients were on prior therapy. There were 2,209 discontinuations during the study time with the main reason being a lack of efficacy (36.4%), followed by remission of the disease (27.2%). In Europe, sometimes patients are treated until remission and then they stop drug. This is not something that we necessarily do here in the United States. The results of this study demonstrated that biologics, especially ustekinumab and infliximab, showed a superior drug survival than classic agents. In conclusion, the number of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in continuous therapy decreases with time for all the systemic drugs included in the cohort, both classical systemic drugs and biologics. There seem to be a high number of factors that influence drug survival rates in psoriasis treatment making survival studies prone to bias and not necessarily the best approach to evaluate drug efficacy and safety in this specific setting, especially when comparing different drugs.

Nevertheless, ustekinumab, across three different studies carried out in very different geographic settings and with different methodology, demonstrated the most durability among the various agents used psoriasis treatment. Whether this is artefact or real may be validly debated.