Antibiotic Stewardship and Isotretinoin

Presented by Guy Webster, MD, PhD

Written by Judy Seraphine, MSc

In this presentation at Maui Derm 2015, Dr Webster discusses the proper use of antibiotics, i.e., “antibiotic stewardship” and how the use of isotretinoin can help us avoid the use of antibiotics.

Dr Webster states that the philosophy of antibiotic use used to be “bacteria are bad, kill them all.” The yang of that philosophy, which we are beginning to appreciate more, is that bacteria are really a part of our personal ecosystem, whether on the skin or in the gut, and that if we mess with our own personal ecosystem, we may cause problems. There’s reasonable data showing that antibiotic use among children at a young age can lead to increased weight gain as they get older due to changes in their flora that become stable.

Remember that antimicrobials are in many soaps and personal products. In fact, 75% of adults have detectable levels of antimicrobials. Topical antibiotics are available over-the-counter and are not regulated (e.g., polymyxin, neomycin, bacitracin). Dr Webster feels that the big problem with antibiotic usage is in farming. The concept here is that antibiotics promote animal growth. The United States uses 29 tons of agricultural antibiotics per year. Resistant strains, as well as antibiotics themselves, can get into wastewater from livestock and poultry farms leading to a potentially altered microbial ecosystem as well as causing disease.

MRSA has also been seen in animals. Strain ST398 was a sensitive Euro human strain that crossed into animals. The use of tetracycline to increase hog weight gave birth to resistant ST398 variants, including MRSA. This strain is now recovered from human infection as well as supermarket beef and pork (30%) and shopping cart handles (10%). There is a clear crossover from the farm to the community. (Nature 499:398, 2013) Data suggest that 30% of farm workers using tetracycline feed have tetracycline-resistant MRSA nasal colonization. On the contrary, only 2% of workers from antibiotic-free farms carry nasal MRSA.

Dr Webster asks us to think about this question—in the face of ongoing agricultural abuses, will what we do with the use of antibiotics make a difference?

The dermatology specialty has a long history of profligate antibiotic usage and until recently, most dermatologists were not study-driven as many diseases are too rare to easily study. We also know that many diseases are said to respond to antibiotics; however, they are not infections (e.g. acne, rosacea, eczema, hidradinitis, bullous pemphigoid).

How do we decide how/when to use a long-term antibiotic?

Long-term antibiotic use is defensible when you are treating a real disease that could harm the patient and clearly responds to antibiotics, and there is nothing more sensible, safe, and/or affordable.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a great example. There are case reports published in several journals supporting the long-term use of antibiotics for GA; however, recent studies have shown little benefit and this is probably something that we, as dermatologists, should stop doing.

Doxycycline is clearly effective for the treatment of mild-to-moderate bullous pemphigoid. It has demonstrated superior safety as compared to prednisone and may be given for years.

Reasonable evidence and randomized controlled trials support the use of doxycycline and minocycline for the treatment of acne. The use of cephalexin, azithromycin, penicillin, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, and TMP/SXT is only supported by anecdote or smaller studies. While many dermatologists prefer personal experience over data, Dr Webster believes that we need to shift away from this and use what has shown to be effective in studies.

The duration of oral antibiotics for the treatment of acne has not been widely studied. Recent guidelines suggest that it should be limited to three to six months. A retrospective cohort study, published in 2014, found that the mean duration of use was 129 days and among the 31,634 courses, 57.8% did not use concomitant retinoid therapy. Although the duration of antibiotic usage is decreasing compared with previous data, some patients are still receiving them for longer periods than they probably need; thus increasing exposure and cost.

Data show that the use of topical retinoid plus an antibiotic is effective for the treatment of acne and after three months, if patients are on the topical retinoid alone, they tend to do as well as those patients who are on combination therapy or an antibiotic alone. The key is to utilize the retinoid from the beginning.

One concern for all clinicians is the development of resistant strains with the use of long-term antibiotics. Unlike the current beliefs about the long-term use of antimicrobial agents, one study found that the prolonged use of tetracycline antibiotics commonly used for acne treatment lowered the prevalence of colonization by S aureus and did not increase resistance to the tetracycline antibiotics. (Antibiotics, Acne, and Staphylococcus aureus Colonization Matthew Fanelli, MD, Eli Kupperman, BA, Ebbing Lautenbach, MD, MPH, Paul H. Edelstein, MD, and David J. Margolis, MD, PhD)

Minimizing Antibiotic Use

Besides giving an antibiotic with a retinoid, you need to consider patient fears, common sense, cost and adverse events. The UK is very concerned about resistance and they tend to use isotretinoin much faster.

Clinical Pearls

- No topical monotherapy

- Add benzoyl peroxide to minimize resistance

- Oral antibiotics should be given with a topical retinoid

- Allows for discontinuation of antibiotic after three months in most

- Earlier switch to isotretinoin or spironolactone when antibiotic + retinoid fails

Isotretinoin Issues

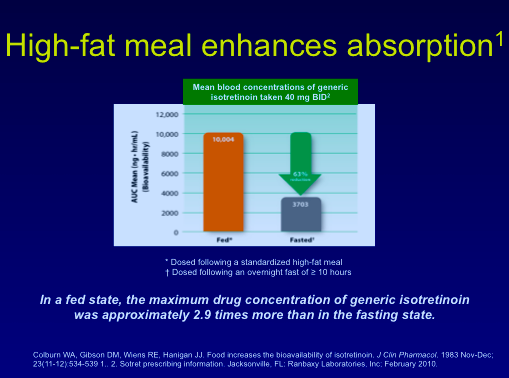

Isotretinoin has been used for many years and, in fact, the longer we use it, the safer we have deemed it to be. Isotretinoin resistance can develop from inadequate dosing, virilization, being taken on an empty stomach, young patients with bad disease, and competing medications. Data show that a meal high in fat increases the absorption of isotretinoin.

Common adverse events (AEs) among patients taking isotretinoin include dry skin, dry lips, high triglycerides and acne flares. Uncommon AEs include elevated CK and elevated AST and ALT. Patients may also experience dry eyes, decreased night vision, depression, and acne fulminans, i.e., an eruption of bad acne in a patient who may have had relatively trivial acne.

Isotretinoin-induced acne fulminans is uncommon, but devastating. It is most often seen early in the treatment of patients, usually on too high of a dose, with moderate-to-severe chest acne. If someone presents with a few nodules on their chest, Dr Webster will often start them at 20mg/day of isotretinoin along with one month of prednisone 20mg/day.

Isotretinoin and bowel disease has become a worry. There have been scattered reports of patients flaring as well as scattered reports of safe usage. Retrospective studies have shown no link or a very weak link between IBD flares and isotretinoin usage. There may; however, be a link between acne and IBD and antibiotics and IBD. (J. Invest Derm 2012, doi:10.1038/jid.2012.387)

Many small studies, although not all adequate, have been conducted looking at the association between isotretinoin and bone mineral density (BMD). A recent study using DEXA found that there was no change from the beginning to the end of isotretinoin treatment in patients’ BMD.

Regarding depression, studies have shown that there are no differences in depression among teens taking isotretinoin versus antibiotics and that there is no greater risk of suicide in isotretinoin versus non-isotretinoin. But, there are always case reports where someone is on the drug and gets depressed, goes off the drug and gets better, then goes back on and gets depressed again. Those outliers probably have something real going on. Studies have been conducted looking at patients with bipolar disease. If you have a known bipolar teen whom you are looking to put on isotretinoin, you may want to consult with the psychiatrist.